iFuse Resources

Rehabilitation for SI Joint Pain and/or Dysfunction

Figure 5 - SI Joint Provocative Tests

Non-surgical treatment of the SI joint isn’t limited to treatment of the joint itself, but also includes treatment of contributing factors that can lead to dysfunction and pain both at the SI joint and in the adjacent muscles, ligaments and joints. As patients with SIJD can be quite different (a 35-year old post- partum female as opposed to a 65-year old male with multiple prior lumbar fusions) there is not a single treatment plan that is right for every patient. The best way to treat SI joint pain with rehabilitation is to identify and then treat the underlying soft tissue impairments. This should be accompanied by symptom relief so that treatment is well tolerated. This treatment plan assumes that the healthcare practitioner has already ruled out pain associated with pathological processes including inflammatory arthritis, infections, tumors and acute fractures with blood tests and diagnostic tests such as x-rays, CAT scans, MRIs, etc.

Rehabilitation for the SI Joint

Goals

Physical therapy, as a profession, is not uniform and there are different schools of thought regarding treatment of SI joint disorders. However, the goals of rehabilitation for SI joint pain typically include:

- Return the SI joint it to its normal position4 and maintain this position. Optimal SI joint function occurs with the SI Joint in neutral (mid-range) position.5-13

- Restore optimal alignment of the lumbar spine, sacroiliac joint and hip joints

- Optimize functional stability of the lumbopelvic region by restoring normal function of the supporting muscles

Evaluation

Prior to treatment the physical therapist performs a thorough evaluation and identifies problems in the following areas that may affect the three goals above:

- General Deconditioning

- Weakness of Stabilizing (Core) Musculature

- Imbalance of muscle length on the muscles that attach to the legs or cross the trunk and pelvis

- Imbalance in muscle strength of the muscles that attach to the legs or cross the trunk and pelvis

- Problems with function, position or motion in the joints above and below the SI joint including the hips and spine directly above and below but also including joints at a distance like the ankle.

- Restriction or scarring in the muscles or tissues that overly or attach to the SI joint

- Poor postural patterns

- Poor and asymmetrical movement patterns with daily activities

- Abnormal or asymmetric walking patterns

- Lack of control of the muscles that coordinate to stabilize the lower back and pelvic region (often called motor control)

- Pain in soft tissues and joints other than and including the SI joint.

Treatment Plan

After the evaluation, the physical therapist will create a treatment plan to address the deficits described above. When creating this treatment plan, the physical therapist takes into consideration the patient’s functional goals. Functional goals are the activities that the patient needs to perform so that they can perform their self-care, occupational and recreational activities in a manner such that they can live with their SI joint dysfunction.

Treatment

There is very little published clinical evidence for any one specific treatment technique for SI joint dysfunction. Physical therapy is a profession, rather than a specific treatment. As such, physical therapists are educated to identify and treat impairments identified during the evaluation based on published research and what is termed “best practice”. The underlying impairments described above are identified and then treated. The goal is to achieve the three functional goals and ultimately assist the patient in achieving pain-free function with their daily activities.

One of the most important aspects of an effective treatment program is patient education. The patient should be educated as to the potential cause(s) of the SI joint dysfunction They should also be educated on how they need to be an active participant in their care. This includes following recommendations to change the way the patient positions themselves, moves during daily self-care and recreational activities, including methods to independently reduce their pain. This may include application of heat or ice, resting when advised, and performing specific exercises.

The patient will frequently be given a home exercise program. This program will be specifically designed to address the impairments of each individual patient. Effective and frequent communication between the patient and physical therapist is important to assure the exercises are within the patient’s pain tolerance and abilities.

Treatment Components

These are the parts of treatment that may help with the alleviation of SI joint dysfunction.

Modification of Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)

- The physical therapist may specifically focus on activities that create or worsen symptoms. These activities typically involve repetitive twisting and asymmetrical motions. They will replace these activities or modify them to eliminate potential strain on the SI joint or the development of impairments in muscle length/strength and joint mobility above, at and below the SI joint.

Patient education regarding maintaining optimal alignment with positioning, posture and body mechanics

The physical therapist will educate the patient regarding the best way to sit, stand, move, sleep, and perform daily activities to prevent body positions that may decrease the ability of the core muscles to function resulting in additional strain on the SI joint. The suggestions may include avoidance of:

- Sitting in asymmetric positions with knees crossed or shifted to one side

- Standing with the knees locked (hyperextended) and weight shifted to one side

- Twisting to one side for long periods or repeatedly: It is better to move the entire torso and prevent this strain on the SI joint especially in the spine if fused if the patient has stiff hips that don’t rotate well

- Sleeping on one side with lack of support under the waist and between the knees. This allows the trunk to bend to one side and may put the spine and hip in an asymmetric position for long periods leading to muscle stiffness/shortness and strain on the SI joint. The PT may advise the patient in the use of pillows or supports to make this position more symmetric.

- The physical therapist may also recommend an SI band or belt for temporary use to compress the SI joints and provide external stability until the patient’s core muscle strength improves and/or to help with treatment tolerance (pain relief).

Achieve normal muscle strength balance (It is important for there to be a balance in the strength of muscles that stabilize the SI joint)17-20

- The PT will instruct the patient in exercises to address any muscles that have weakened because of chronic SI joint pain. This includes the Gluteus Medius muscle which often becomes weak on the painful side. This muscle may affect balance while walking.

- The PT may instruct the patient to strengthen muscles that affect the position or the mobility of the SI joint These muscles may be in the legs, trunk, or hip region. The goal is to have equal muscle strength on each side of the joint.

Balance assessment and training

- Long term pain in the sacroiliac joint may cause an imbalance in the muscles or a stiffness in the surrounding joints that may affect the patient’s balance. The therapist, may develop a program to address the underlying cause of these balance issues. They may also use specific balance training exercises.

Gait training

- Pain in the SI joint and/or dysfunction may alter the patient’s gait (walking) pattern. The patient may take a shorter step, elevate the painful side leg using the trunk muscles and may hold the leg on the painful side in a turned-out position. As the patient’s symptoms improve, the physical therapist will assist with educating the patient to eliminate these gait alterations as they may lead to additional pain or dysfunction at, above or below the SI joint.

Regain or maintain cardiovascular health

- Long term pain and/or dysfunction at the SI joint may inhibit a patient’s ability to participate in aerobic activity. Aerobic activity such as walking, jogging, rowing, biking, swimming, or using an elliptical machine is important to maintain a healthy heart and lungs (cardiovascular system). A physical therapist can assist with determining the best aerobic activities to maintain cardiovascular health without putting excessive stress on the symptomatic SI joint.

Most patients notice some improvement in their symptoms within the first several physical therapy visits and may continue to improve until they achieve pain free function. If the patient does not have adequate improvement in their symptoms with rehabilitation and other non-surgical treatment methods within 6 months, then additional evaluation and treatment may be indicated.

IMPORTANT NOTE: The information herein is intended to help create awareness about Rehabilitation for SI Joint Pain and/or Dysfunction. Please note that information contained herein is not medical advice. It should not be used as a substitute for speaking with your physician. Always talk with your physician about diagnosis and treatment information.

References

- Solonen KA. The sacroiliac joint in the light of anatomical, roentgenological and clinical studies. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica Supplementum. 1957;27:1–127. PMID 13478452.

- Fortin JD, Falco FJ. The Fortin Finger Test: An Indication of Sacroiliac pain. Am J Orthop (Bell Mead NJ). 1997 Jul;26(7):477-80.

- Laslett M. Evidence Based Diagnosis and treatment of the painful Sacroiliac Joint. J Man Manip Ther. 2008;16(3):142-52.

- Fife S. J Man Manip. 2008;16(4): E102. (Comment on Laslett – J Man Manip. 2008; 16:142-52.)

- DonTigny RL. Anterior dysfunction of the sacroiliac joint as a major factor in the etiology of idiopathic low back pain syndrome. Phys Ther. 1990;70:250–65.

- DonTigny RL. Critical analysis of the functional dynamics of the sacroiliac joints as they pertain to normal gait. J Orthopedic Medicine. 2005;27:3–10.

- DonTigny RL. Critical analysis of the sequence and extent of the result of the pathological failure of self-bracing of the sacroiliac joint. J Man Manip Ther. 1999;7(4):173–181.

- DonTigny RL. Function of the lumbosacroiliac complex as a self-compensating force couple with a variable, force dependent transverse axis: A theoretical analysis. J Man Manip Ther. 1994;2:87–93.

- Fujiwara A, Tamai K, Kurihashi A, Yoshida H, Saotome K. Relationship between morphology of iliolumbar ligament and lower lumbar disc degeneration. J Spinal Disord. 1999;12(4):348-52.

- Pool-Goudzwaard A, Van Dijke GH, Mulder P, Spoor C, Snijders C, Stoeckart R. The iliolumbar ligament: Its influence on stability of the sacroiliac joint. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2003; 18:99–105

- Snijders CJ, Hermans PFG, Niesing R, Spoor CW, Stoeckart R. The influence of slouching and lumbar support on iliolumbar ligaments, intervertebral discs and sacroiliac joints. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2004;19:323–9.

- Snijders CJ, Vleeming A, Stoeckart R. Transfer of lumbosacral load to iliac bones and legs. Part 1: Biomechanics of self-bracing of the sacroiliac joints and its significance for treatment and exercise. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 1993;8(6):285-94.

- Vleeming A, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Stoeckart R, van Wingerden JP, Snijders CJ. The posterior layer of the thoracolumbar fascia. Its function in load transfer from spine to legs. Spine. 1995;20:753–8.

- Snijders CJ, Vleeming A, Stoeckart R. Transfer of lumbosacral load to iliac bones and legs. Part 2: Loading of the sacroiliac joints when lifting in a stooped posture. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 1993;8:295–301.

- Hodges PW, Richardson CA. Inefficient muscular stabilization of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain. A motor control evaluation of transversus abdominis. Spine. 1996;21(22):2640-50.

- Richardson CA, Snijders CJ, Hides JA, Damen L, Pas MS, Storm J. The relationship between the transversely oriented abdominal muscles, sacroiliac joint mechanics and low back pain. Spine. 2002;27(4):399-405.

- Lee DG, Vleeming A. Impaired load transfer through the pelvic girdle- a new model of altered neutral zone function. In: Proceedings from the 3rd interdisciplinary world congress on low back and pelvic pain. Vienna, Austria. 1998

- Vleeming A, Stoeckart R, Volkers ACW, Snijders CJ. Relation between form and function in the sacroiliac joint. Part 1: Clinical anatomical aspects. Spine. 1990;15(2):130-2.

- Vleeming A, Stoeckart R, Volkers ACW, Snijders CJ. Relation between form and function in the sacroiliac joint. Part 2: Biomechanical aspects. Spine. 1990;15(2):133-6.

- Vleeming A, Van Wingerden JP, Snijders CJ, Stoeckart R, Stijnen T. Load application to the sacrotuberous ligament; influences on sacroiliac joint mechanics. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 1989;4(4):204–9.

- Cibulka M, et al. Unilateral Hip Rotation Range of Motion Asymmetry in Patients With Sacroiliac Joint Regional Pain. Spine. 1998;23(9):1009-15

- Szadek KM, et al. Diagnostic Validity of Criteria for Sacroiliac Joint Pain: a Systematic Review. J Pain. 2009;10(4):354–368.

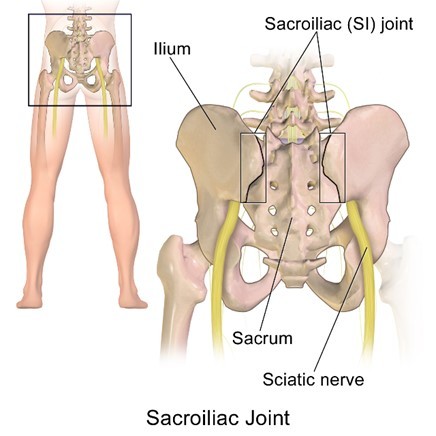

Figure 1 image credit : Blausen.com staff (2014). "Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014". WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436. - Own work image

10228.091118